What to Say (or Not to Say) When Someone is Fired for Sexual Harassment

It is Friday at 5:00 p.m. and you've just had to terminate a supervisor in your organization after an internal investigation revealed he had engaged in sexual harassment. The termination meeting went about as well as could be expected—the supervisor was angry, but you were on solid ground under the company's discipline policy. You leave work feeling confident the situation has been handled.

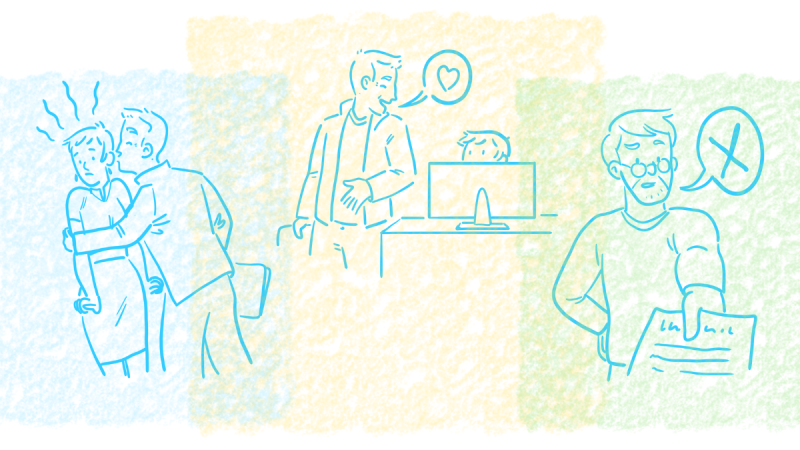

But when you walk into your office on Monday morning, you've got three messages waiting. The first is from a local reporter, who is doing a story on the #MeToo movement in your industry, and has recently heard about how a top-level employee at your organization was fired for sexual assault. The next is from a manager who is wondering what to say to his team about the firing. Finally, the former supervisor has apparently already applied for a new job, and his prospective employer has called for a reference. How should you respond?

If you feel overwhelmed by this scenario, you are not alone. Properly handling sexual harassment allegations is difficult and legally risky. And even if you are confident the complaint was properly addressed—for example, by terminating a problem employee—a big legal problem still remains: what should the organization say after someone is fired for sexual misconduct? This article explores some of the sticky moral and legal issues in this area and discusses the many factors that come into play when making post-termination statements.

Ways the Organization May Get Criticized or Face Legal Risk

Ministries and businesses may face criticism on social media or in the press, and even legal claims, for a variety of actions and inaction. Here are some of the most common.

- Critics argue that the organization was too lenient.

In one case, a CEO was accused of sexual harassment, which was substantiated by an investigation by a law firm. The organization was criticized publicly because he was allowed to resign and got over $500,000 in a severance agreement, plus an ongoing advisory relationship.[1]

Another case involved a senior employee leaving Google after being accused of sexual harassment. Google allowed him to leave. He was hired by Uber. He denied that the allegations were true. However, he was asked to leave Uber. Neither organization would comment.[2] (It does not appear that the allegations were ever established by an investigation.)

- Disclosing harassment can create legal claims for defamation.

A public statement about sexual harassment can impact someone's personal and professional career. If not true, the statement could be defamation. When it's about sexual harassment, it could be "defamation per se," which presumes the reputational harm (and the person does not have to prove the harm).

Some states protect the victim's right to make statements about their own experiences. And some states protect employers' rights to give a truthful reference about an employee. But some states don't protect statements like this, or the protection is weak enough that there could still be painful and expensive litigation.

In one case, a professor at a Christian college was terminated after a six-month investigation into sexual harassment allegations from students. The university made a public announcement disclosing that the investigation found inappropriate conduct. The professor filed a lawsuit for wrongful termination and reputational damage. He also alleged that the investigation was fundamentally flawed.[3] It seems there may also have been similar complaints at another Christian college.[4]

In another case, a senior government worker sued a former colleague for defaming him publicly, and also the organization for not investigating according to best practices.[5] The court allowed the claim to go forward that the government had violated his procedural due process rights by not telling him about the allegations or interviewing him.[6]

- Not disclosing harassment can create negligent referral claims.

A negligent referral lawsuit could be brought by a future employer or by a person harmed, if the employer withholds important negative information. When an employer knows about harassment and gives a positive reference, there could be trouble.

For example, in a school case, an administrator was forced to resign after sexual misconduct allegations. The district provided glowing letters of recommendation. This is called colloquially, "passing the trash." The administrator went on to sexually abuse a 13-year-old student elsewhere. The California Supreme Court allowed the victim's lawsuit to proceed on the theory that the district had misrepresented the facts and concealed a known risk.[7] The court noted that there is no general duty to volunteer negative information, but if you choose to provide recommendations, you cannot mislead by leaving out negative information.

- Hunting the person down can create blacklisting and interference claims.

In some states, statutes prohibit employers from intentionally interfering with future employment by providing false and malicious references. Statements to future employers must be truthful and made in good faith. However, it is particularly risky to seek out future employers, which can bring organizations within the scope of these statutes.

- Wrongfully requiring non-disclosure provisions can create legal claims.

A number of laws restrict or prohibit nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) in settlement involving sexual harassment, sexual assault, or sexual abuse. The laws are intended to keep employers from silencing victims and to help prevent repeat offenders from moving on with impunity. These laws include the federal Speak Out Act of 2022, which applies to NDAs signed before a legal action arises, and various state laws, such as Trey's Law, that may prevent NDAs related to the facts of sexual harassment/abuse allegations in all circumstances.

Setting Up the Termination Properly

- Investigate appropriately and terminate on solid grounds.

Provide the accused employee with due process before a finding is made. In cases where the allegations are disputed, it is important for the organization to perform a thorough investigation and consider all the relevant evidence, before reaching a finding about the allegations and taking action. It's worth noting that a recurring theme in the defamation cases is that the investigation wasn't complete or fairly carried out.

An individual facing allegations of sexual harassment may well have committed those offenses. If so, he or she should be disciplined appropriately. But if a finding is not reached, the person should not be disciplined on that basis. (It may be that there are other legitimate grounds for termination, or the situation can be addressed by additional training or a safety plan.)

- Don't make unsupported statements.

Simply firing the employee and then reporting that the employee is a harasser can lead to liability and trouble for the organization. Making statements about allegations before they are confirmed or beyond what has been confirmed is not good practice, both from a legal liability perspective and considering simple fairness to the accused. Publishing allegations can stigmatize an individual, follow the person forever, and lead to liability for the organization in the form of defamation or similar tort lawsuits, etc.

Telling the Organizational "Family"

Customers, vendors, fellow employees or other people who worked regularly with the former employee may be some of the first to ask what happened. This organizational "family" may feel they have a right to know what is happening in their organization. (This may be particularly true in the ministry context.) Some may have been involved in the internal investigation that led to the termination and desire an update. The organization may want to reassure those who remain that the company was tough on sexual harassment. Or speculation may be circulating about "the real reason why so-and-so was fired," and the organization may need to do damage control.

When making statements to this group, consider the following points:

- Be aware of qualified privilege.

Employers have some rights to discuss employment issues within the organization. Evaluations, investigative reports, employee discipline, and termination documents usually fall under a qualified privilege. The persons who need to be involved in these discussions will usually be protected. Once private personnel matters start to get spread through the organization, the qualified privilege usually disappears.

- Consider designating an internal spokesperson.

Control information by ensuring any statements are handled by a designated HR spokesperson, in collaboration with other key higher-level employees. In general, it is better to have the message communicated by one office or individual, rather than leaving it up to a larger group to disseminate an inconsistent message with varying level of detail. If the organization is speaking, whether through HR, the President, or a high-level supervisor, it is potentially making a record that could be used in future litigation.

- Be cautious about how much is said, and to whom.

In terms of how much to say, in general, an organization can say a bit more internally than it should to outsiders. There is a different legal relationship between current employees and their employer than those outside that circle. Employers may have good reason to give out some information. The alleged victim is usually entitled to a brief summary of whether her allegations were accepted, even though not to details about employee discipline.

The organization's ability to require complete confidentiality may also be limited due to the National Labor Relations Act, which generally allows employees to discuss the terms and conditions of their employment with each other and outsiders. However, be sensitive to the fact that internal statements—particularly those made in writing or recorded—can quickly find their way outside.

The appropriate amount of information should also vary depending on the different stakeholders involved. A general company-wide statement may look quite different than a memo to a small group of supervisors. One approach may be to provide sexual harassment training that addresses similar situations, without mentioning names. This shows people that the organization takes claims seriously without providing personal details. When in doubt, and particularly if a lawsuit seems possible, consult legal counsel.

- Don't give out false information.

It is not a good idea to make up an excuse for why someone was fired. Not only does this have the potential to create confusion (and backlash if it gets out), but it can backfire later in the event of litigation. For example, if a company tells the remaining employees that a former supervisor was fired for missing work (when it was really sexual harassment that was the cause), it may create confusion and prolong litigation when the motivation behind the termination is examined.

When a Future Employer Comes Calling

Another related question arises when a former employee's new potential employer contacts the organization seeking a reference for the employee who was terminated for sexual misconduct. How much can be shared? This is a question with both legal and moral implications. There may be legal risks in sharing, but the organization may feel a moral responsibility to past victims and to future vulnerable people. Here are some approaches to consider.

- Put policies in place in advance to address the issue.

With proper planning, employee references can be dealt with uniformly for all employees. A uniform policy usually defaults to the minimum statement that the person worked there: name and dates of employment, title, and rate of pay. Most employment attorneys recommend this limited approach due to risks of litigation.

- Be aware of the privileges.

In some jurisdictions, the organization may have a qualified privilege or immunity to share information with future employers. Evaluate this with the help of legal counsel before sharing information.

- Consider the risks involved in a "duty to warn."

Some ask whether a former employer has a duty to inform a future employer about the known proclivities of a former employee. In a few contexts—where there has been child sexual abuse, for instance—the former employer's failure to warn or give notice to a future employer could lead to litigation if someone at the new employer is later harmed. However, this usually is limited both to scenarios where there has been serious crime and/or where there is a very close organizational connection between the old and new employers.

While the "duty to warn" concept has been pushed by victim advocates, criminal charges and civil lawsuits will probably continue to be the appropriate way to handle such matters. One reason for this is that employers only have to make a reasonable finding to a preponderance of the evidence to terminate someone. It offends our society's notions of justice that an informal proceeding like this will follow someone to other settings and increases the risks of litigation.

- Consent creates an "absolute privilege" to share.

If a future employer would like to know about an employee, and if the organization has strong moral reasons to share, such as where there has been sexual harassment or child abuse, one useful tool is the waiver of liability for a reference. The organization can explain that they will share candidly about the ex-employee if the ex-employee agrees to sign a waiver of liability related to such sharing. Usually, where there has been serious moral failure, the ex-employee will not sign the waiver. And that is an important data point for the prospective employer as well.

- A limited statement may also work well.

There are some good questions for future employers to ask, that would not implicate defamation. One is, "Is this person eligible for rehire?" Another is, "Would you personally entrust this person with care of your children/grandchildren?" It is easy to defend factually whether a person is eligible for rehire, as that should be flagged in the personnel files. Whether you would trust someone with your child is pure opinion, but it can be helpful to know that someone has this opinion.

- Ministries may have a religious First Amendment right to share.

Churches and other ministries should have strong statements related to harassment and discrimination, child abuse, and moral failure. They may have a theological position that they are obligated to warn future employers, particularly about child abuse and sexual harassment. (It's helpful if this position is part of their policies, and the employee has acknowledged it previously.) Ministries may choose to exert a "free exercise" right to share information.

If they do, the information should be shared carefully in a limited way, such as directly with another spiritual leader. Sharing the information should be specifically framed as a religious communication in pursuit of religious practice. If there is a close association with the other organization, the risk is somewhat less, but it is likely more if there is no connection.

Sometimes, protecting other vulnerable people requires a person or an organization to take a risk, but it should be done carefully, with support from legal counsel.

The Public's Right to Know?

One of the most striking shifts in recent years is how formerly internal HR matters have quickly become matters of public concern. With this shift toward the public demanding more transparency from organizations, several issues for employers arise. Is the organization legally obligated to inform the public? Even if not, does the "court of public opinion" require disclosure?

- Private companies and ministries generally should not publicly disclose internal HR matters.

Generally, private organizations are not required or even permitted to inform the public about internal employee discipline. There is no legal obligation to confirm or deny allegations of sexual misconduct to the public. Not only that, but organizations have no legal right to share internal employee affairs or information from personnel files. This could violate several laws around privacy and data protection. The organization could face a lawsuit for defamation, invasion of privacy, violation of privacy laws, or other similar claims.

- Seek counsel before making a public statement.

Sometimes, public pressure to make a statement pushes organizations in that direction. There are several considerations when making a statement. One consideration is whether the allegation is already public knowledge, such as through a law enforcement action. Another is whether it is already public in settings such as social media.

There may be some value to making a statement to clarify as a response to other publicity, but it shouldn't be done without counsel. The exact language used may be key.

- When in Doubt, Seek Advice Before You Speak

Because of the myriad legal issues that might pop up after a termination, particularly if sexual harassment or other sexual misconduct is involved, making statements is not a DIY exercise. First, consider the organization's moral position and what it believes should be said to protect people, Then, seek legal counsel to evaluate the liability risk of making a particular statement. In some cases, it may also be advisable to check with a media consultant to get the messaging right, avoiding statements that are insensitive about those who may have been harmed, or that violate due process or privacy laws. Careful consideration may help avoid a major crisis.

________________

[1] https://nypost.com/2026/03/01/us-news/calif-water-ceo-steps-down-amid-harassment-findings-scores-512k-pay-deal

[2] https://www.businessinsider.com/amit-singhal-leaves-uber-over-harassment-allegations-2017-2?op=1

[3] https://globalnews.ca/news/11164804/fired-professor-lawsuit-crandall-university

[4] https://www.hcamag.com/ca/specialization/employment-law/professor-claiming-wrongful-dismissal-told-he-must-first-provide-more-information

[5] https://nypost.com/2025/05/03/us-news/ex-biden-nuclear-official-who-restored-oppenheimer-clearance-alleges-conspiracy-to-oust-him-over-sex-harassment-allegations

[6] https://cases.justia.com/federal/district-courts/district-of-columbia/dcdce

[7] Randi W. v. Muroc Joint Unified Sch. Dist, 14 Cal. 4th 1066 (Cal. 1997).

Because of the generality of the information on this site, it may not apply to a given place, time, or set of facts. It is not intended to be legal advice, and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations