An Exceptional Case: The Supreme Court’s Recent Ministerial Exception Decision

On July 8, 2020, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down its decision in the case of Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrisey-Berru.1 This case involved two former Catholic school teachers, Agnes Morrisey-Berru and Kristin Biel, each of whom taught at different Roman Catholic schools in the Los Angeles, California area. Both teachers were terminated by their respective schools and both teachers sued their respective schools for unlawful discrimination. Morrisey-Berru sued for age discrimination and Biel sued for disability discrimination.

As a defense to the teachers’ claims, both of the Catholic school employers asserted that the teachers’ claims should be dismissed by application of the so-called “ministerial exception,” a doctrine based on the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In this doctrine, churches and religious organizations are immune from employment lawsuits from employees who are “ministers” because they are free to choose their ministers. The central issue in this case was whether to the plaintiffs were “ministers” for purposes of the ministerial exception. In a 7-2 decision, the Court ruled that both employees were ministers. In doing so, the Court clarified the criteria for determining whether an employee is a “minister.”

Background: Hosanna Tabor v. EEOC

To appreciate the significance of the Our Lady decision, it is important to understand an earlier Supreme Court decision, Hosanna Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC.2 While the ministerial exception had been applied by lower state and federal courts for several decades prior, Hosanna-Tabor was the first time the Supreme Court applied the ministerial exception.

Hosanna Tabor involved a teacher at a Lutheran school, Cheryl Perich, who, like Morrisey-Berru and Biel, was terminated and sued her former employer for unlawful discrimination. The Supreme Court unanimously decided that Perich was a minister under the ministerial exception and that her claims against the school were barred.

The Court affirmed the existence of the ministerial exception but declined “to adopt a rigid formula deciding when an employee qualifies as a minister.” Rather, in its determination that Perich was a minister, the Court analyzed its determination of her ministerial status. First, the Court pointed to the fact that the Lutheran school held Perich out as a minister. Second, the Court noted that Perich’s job title was that of “Minister of Religion.” Third, the Court said that Perich held herself out to be a minister. Fourth, the Court found that Perich’s job duties included important religious functions such as leading prayers and teaching the Lutheran faith. These four considerations led the Court to conclude that Perich was a minister.

A Narrow Exception?: The Ninth Circuit’s Interpretation of Hosanna-Tabor

When Biel and Morrissey Berru sued their respective former employers, the trial court in each case applied the ministerial exception, ruled that both teachers were ministers, and dismissed their claims. However, both teachers appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. In each case, the Ninth Circuit reversed the trial court’s decision and ruled that neither employee met the qualifications for being a “minister.”

In reaching its decision in each case, the Ninth Circuit interpreted the Supreme Court’s decision in Hosanna-Tabor to require an employer to prove additional facts supporting an employee’s ministerial status above and beyond the employee’s performance of religious duties or functions. The Ninth Circuit understood the four “considerations” that Supreme Court discussed in Hosanna-Tabor to be a four-factor test under which a court needed to make the following inquiries to determine whether an employee was a minister: (1) whether the employer held the employee out as a minister, (2) whether the employee's title reflected ministerial substance and training, (3) whether the employee held herself out as a minister, and (4) whether the employee's job duties included important religious functions.

Under the Ninth Circuit’s interpretation of Hosanna-Tabor, in order to be a “minister” for purposes of the ministerial exception, an employee essentially had to closely resemble the plaintiff from Hosanna-Tabor, and have formal training and an official ministerial title. Applying these four factors to Biel and Morrissey-Berru, the Ninth Circuit ruled that, based on a strict comparison, neither Biel nor Morrisey-Berru were ministers. While both teachers performed religious functions such as leading prayers and teaching subjects with some reference to Catholic doctrine, neither had formal theological training or an official ministerial title. In an opinion dissenting from the rest of the court, one Ninth Circuit judge objected that the court had “embraced the narrowest construction of the First Amendment’s ministerial exception.”

The Supreme Court’s Rejection of the Ninth Circuit’s Rule

Both Catholic school defendants appealed to the Supreme Court, which granted review and consolidated both cases into one matter.

The Supreme Court reversed the decision, explaining that while the Court in Hosanna-Tabor had articulated several factual considerations on which it had concluded that Cheryl Perich was a minister, the Court’s “recognition of the significance of those factors in Perich’s case did not mean that they must be met—or even that that they are necessarily important—in all other cases.”

Factors such formal titles and academic credentials could not be imposed as requirements for ministerial status, as this would effectually make the ministerial exception operate in favor of established Christian sects as opposed to other faith traditions where ministers were not typically characterized by titles or training. Rather, “what matters at bottom, is what an employee does.” This was a decisive rejection of the Ninth Circuit’s narrow view of the ministerial exception and a recognition that “religious function” is the touchstone for determining ministerial status.

Duties or Deference?: Implications of Our Lady and the Future of the Ministerial Exception

However, while the Court clearly ruled out the Ninth Circuit’s view as a viable standard for determining ministerial employment, the decision leaves open the issue of how much deference a court should give to a religious employer’s assertion that an employee is a minister.

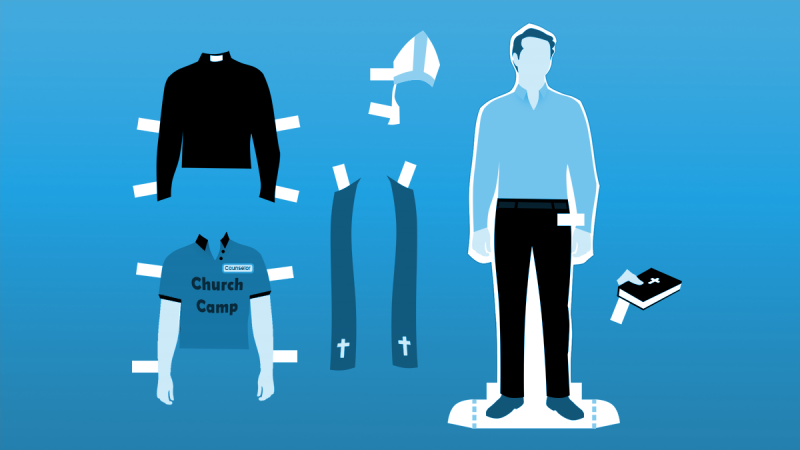

When a court inquires into whether an employee performs “important religious functions,” it must do so on a presupposed definition of the word “religious.” What job duties qualify as “religious?” While clergy and teachers at religious schools are now considered well within the ministerial exception, where is the boundary of the exception’s application? Are nurses at religious hospitals who minister to their patients both medically and spiritually covered by the exception? What about camp counselors, sports coaches, social-service workers, and many other employees of religious institutions? How far does the exception extend?

“The decisions from this year’s Supreme Court term have been somewhat of a roller coaster for conservative religious organizations. In the Court’s recent decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, the Court ruled that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbids employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. For faith-based organizations operating with traditional religious convictions, the Court’s decision in Our Lady may off-set the effects of the Bostock decision, providing broader Title VII immunity, at least with respect to their selection of ministers."

Considering another dimension of the exception’s scope, does it only apply to employment discrimination laws or does it extend to other workplace regulations such as wage and hour laws, occupational safety, unemployment insurance, etc.? Does it apply as a defense to workplace torts such as defamation and invasion of privacy? While these are questions that the Supreme Court has yet to answer, its recent decision in Our Lady nonetheless has significant implications both for faith-based employers and their employees.

_________________________________________

1 Access the Court’s full opinion for this decision at: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/19-267_1an2.pdf.

2 565 U. S. 171 (2012). Access the opinion from this decision at: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/565/171/.

Featured Image by Rebecca Sidebotham.

Because of the generality of the information on this site, it may not apply to a given place, time, or set of facts. It is not intended to be legal advice, and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations