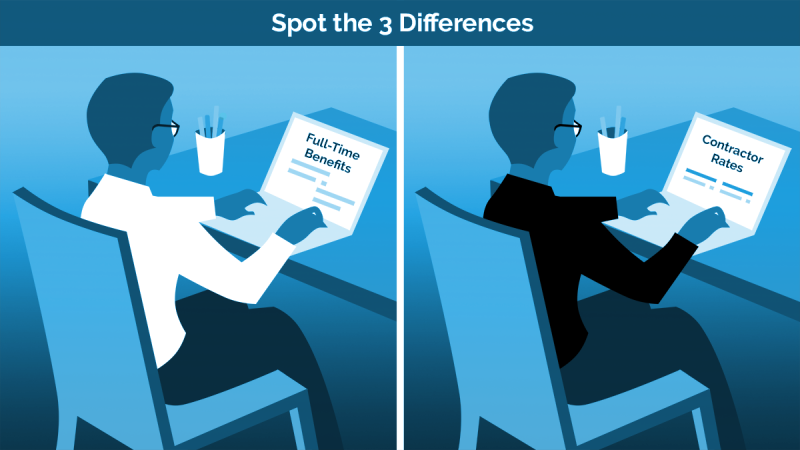

Is Your Independent Contractor Really an Employee? Take a Closer Look at the Rules

Is your worker an independent contractor or employee? For an independent contractor, the company does not have to pay workers' compensation or unemployment insurance premiums, withhold federal and state income taxes, or pay its share of employment taxes. In addition, in many states, independent contractors cannot file discrimination claims.

So, companies would often like to avoid classifying workers as employees and make them fit as independent contractors. But simply designating someone an independent contractor is not enough if you are treating them like an employee. And getting this classification wrong can lead to trouble. It's important to understand that just because workers are paid off the books, receive a 1099, or even agree—verbally or in writing—to be classified as an independent contractor, including by signing an independent contractor agreement, they still may not be an independent contractor under the law. The actual working relationship and how the work is performed are what matter, not just the label or paperwork. Misclassification can have significant legal and financial consequences.

This blog discusses some of the rules around classifying workers under Colorado and federal law.

I. Why Does Status Matter

The distinction between employees and independent contractors isn't just a matter of titles—it determines who is protected by federal and state labor laws. Employees are entitled to certain safeguards under the FLSA, including the right to receive at least the federal minimum wage and overtime pay for any hours worked over forty in a workweek. These rules are in place to ensure employees are fairly compensated and protected from exploitation in the workplace. Also, at play are anti–discrimination laws that apply to employees and other benefits—such as employer–provided benefits, unemployment insurance, sick and family leave, or workers' compensation coverage—that employees may receive under state or federal law.

Independent contractors, on the other hand, stand outside these protections in most states, with some exceptions. Since they are considered to be running their own businesses, they are responsible for negotiating their rates and terms and providing their own insurance and benefits.

For businesses, it is important to accurately classify workers to avoid inadvertently denying employee protections and benefits where they are due. Misclassifying workers can lead to significant expenses, penalties, and legal headaches down the road.

II. Federal Law on Independent Contractors

When looking at federal law—specifically the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)—the question of whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor isn't decided by simply reviewing what the contract says or by following common law notions of "control." The Department of Labor (DOL) makes rules about this. And worse, it keeps changing the rules.

The current rule in effect as of the time of this writing (in July 2025) dates to May 2024. The DOL has an "Economic Reality Test," which evaluates six factors, none of which is controlling. The overall point is whether the worker is economically dependent on the possible employer. The DOL consider "the totality of the working relationship."

These are the factors, quoted from their website:

- Opportunity for profit or loss depending on managerial skill,

- Investments by the worker and the employer,

- Permanence of the work relationship,

- Nature and degree of control,

- Whether the work performed is integral to the employer's business, and

- Skill and initiative.

If you think this sounds ambiguous, you are not alone in thinking so. This standard has been challenged in court, and rumor has it that the DOL is going to scrap this standard and issue new regulations.

In fact, the DOL has announced that it is not going to enforce the current rule, but go back to an earlier standard. The main differences in the earlier standard are that it looks at the degree of independent business organization as well as the initiative and judgment involved in open market competition, thereby making the analysis a bit easier for the employer. However, private litigation would still be conducted under the current standard, so employers have to consider BOTH standards.

In short, when evaluating independent contractor status under the FLSA, it's not just about labels or paperwork. The focus is on the real–world relationship and whether the worker is truly in business for himself or herself, or instead is economically tied to the company.

III. Colorado State Law on Independent Contractors

For Colorado state law, classification as an independent contractor affects whether you have to pay unemployment insurance premiums, workers' compensation premiums, and FAMLI Act premiums for that individual. Under the Colorado Employment Security Act, as a general matter, an individual is an independent contractor if (1) "such individual is free from control and direction in the performance of the service, both under his contract for the performance of service and in fact," and (2) "such individual is customarily engaged in an independent trade, occupation, profession, or business related to the service performed" (C.R.S. § 8–70–115 (1)).

Businesses must ensure that anyone classified as an independent contractor meets these requirements, both under any contract, and in reality. So how is this done in practice?

IV. Skill and Business Initiative: Beyond Just Technical Ability

Being highly skilled in a particular line of work—say, welding, graphic design, or accounting—does not automatically make someone an independent contractor. What matters is whether the worker uses those skills in operating a business that demonstrates initiative and independence.

For example, a skilled welder who simply follows instructions at a single job site, does not make business decisions, and relies on the employer for what to do and when, is likely to be considered an employee. The point is that the welder, while technically proficient, is not using those skills to build a business or obtain work independently.

Contrast this with a welder who offers specialty welding services—like custom aluminum work—to several construction companies in the area. If that welder markets his skills to attract new business, manages his own workflow, and actively seeks out multiple clients, these facts indicate independent contractor status. The distinction lies not just in technical skill, but in the use of those skills to support or grow an independent business.

By focusing on both the degree of control and the worker's business initiative, you can better determine whether an individual truly qualifies as an independent contractor.

V. Meeting the Requirements Under Federal Law

Merely signing an agreement that labels someone as an independent contractor does not, by itself, guarantee that status under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) or other federal law. The way the working relationship actually functions is what determines classification—not just what's written on paper or verbally agreed to.

Courts and government agencies will look past the contract's label and closely examine the real–world facts: how much control the business exerts over the worker, the degree of independence, and other practical realities of the engagement. So, while a thoughtfully drafted contract is helpful, it's the day–to–day dynamics of the relationship that ultimately decide how the worker is classified under federal law.

One good piece of news is that if the contract is solid under Colorado law, it likely meets federal standards as well. This is true for a number of states. In states with more relaxed standards, it works the other way—a contract that satisfies the federal standard will likely satisfy the state standard.

VI. Meeting the Requirements in Contract in Colorado

If you are classifying an individual as an independent contractor, having a contract outlining your agreement is beneficial. First, it helps make your mutual promises clear. But more importantly, it can help you defend the classification in the event of a challenge. If a challenge arises, the presumption may be that a worker is your employee, as it is in Colorado. Under the Colorado statute, a company can shift that burden if it has a proper contract. This does not guarantee that the government won't challenge your classification. It just shifts the burden of proof for such a challenge so that the government has to prove you misclassified the person rather than you having to defend your actions.

But not any contract will do. Under the statute, in order to shift the burden, the written independent contractor agreement agreed to by both parties must contain assurances of what the company will not do, and a disclosure.

First, the contract has to contain assurances that the company will not do the following (Quoted from C.R.S. § 8–70–115 (1)(c)):

- Require the individual to work exclusively for the person for whom services are performed; except that the individual may choose to work exclusively for the said person for a finite period of time specified in the document;

- Establish a quality standard for the individual; except that such person can provide plans and specifications regarding the work but cannot oversee the actual work or instruct the individual as to how the work will be performed;

- Pay a salary or hourly rate but rather a fixed or contract rate;

- Terminate the work during the contract period unless the individual violates the terms of the contract or fails to produce a result that meets the specifications of the contract;

- Provide more than minimal training for the individual;

- Provide tools or benefits to the individual; except that materials and equipment may be supplied;

- Dictate the time of performance; except that a completion schedule and a range of mutually agreeable work hours may be established;

- Pay the individual personally, but rather makes checks payable to the trade or business name of the individual; and

- Combine his business operations in any way with the individual's business, but instead maintains such operations as separate and distinct.

In addition to including the statutory factors, the contract must contain a required disclosure. The disclosure must state, "that the independent contractor is not entitled to unemployment insurance benefits unless unemployment compensation coverage is provided by the independent contractor or some other entity, and that the independent contractor is obligated to pay federal and state income tax on any moneys paid pursuant to the contract relationship." It must also be in larger type than the rest of the contract or in bold or underlined.

Meeting the statutory standards will get you the presumption that the person is an independent contractor. And if you don't meet all the statutory standards, you can still argue that the person is an independent contractor, but the burden of proof is now on you.

Either way, a lawyer can help you draft such a contract, but in the end, it may not help if the contractual provisions do not match up with reality. Having a contract that outlines these requirements is not sufficient if the actual working relationship does not follow suit. So make sure your actual working relationship with an individual in fact meets the standard for an independent contractor under Colorado law.

VII. Meeting the Requirements in Fact

A good first step to check proper classification is to review state and federal standards to see where your working relationship falls. Remember, you are looking at the "totality of the circumstances." If your company's working relationship with an individual looks more like an employee–employer relationship, chances are, it probably is. In the "quacks like a duck" test, even fairly minor considerations like whether the independent contractor has his or her own business card or business phone number may be relevant.

A. Permanence in the Work Relationship

The contract should avoid language or terms that imply a high degree of permanence or exclusivity in the working relationship. A true independent contractor typically maintains a business that serves multiple clients and is free to accept or decline work from any company. For instance, if a contractor works continuously and exclusively for your business—say, a designer who only takes on your projects for years and turns down all other opportunities—this could weigh in favor of employee classification. On the other hand, if the contractor routinely markets its services, takes on projects from various clients, and only occasionally works with your business (even if over several years), this sporadic, nonexclusive relationship supports independent contractor status. Any exclusivity should be the result of the contractor's own business decision for a limited, contractually defined period, not a requirement imposed by your company.

B. Work Integral to Your Business

To better understand how "integral" work factors into classification, consider a couple of practical scenarios.

Imagine a vineyard during harvest season. The business depends heavily on seasonal workers to pick grapes—without them, there'd be no wine to sell. Grape picking isn't just helpful, it's essential to the vineyard's core operations. Because the business revolves around this activity, those pickers are likely to be classified as employees under the "integral to the business" standard.

Contrast this with the vineyard's decision to hire a graphic designer to update its logo or a CPA to prepare annual tax returns. While these professionals provide valuable, even necessary, services, their work isn't central to grape growing or wine production. The vineyard could, in theory, function day–to–day without their support. Hiring this kind of professional, whose contribution is peripheral rather than fundamental, typically weighs in favor of independent contractor status.

The closer a worker's duties align with the core of the business, the greater the risk that he or she will be classified as an employee.

C. Managerial Skill and Decision–Making

Does the individual truly have an opportunity for profit or loss based on managerial skill? In other words, does the worker have real authority to make independent business decisions that can increase profits or expose them to a financial loss? This assessment is central to distinguishing employees from independent contractors.

Here's what to look for:

- Independent Decision–Making: If the worker has the freedom to set her own rates, negotiate her own contracts, or determine which projects to take on, she's exhibiting the hallmarks of a business owner or independent contractor. For example, a freelance graphic designer who negotiates project fees, advertises services, invests in her software and equipment, and decides whether to hire an assistant clearly demonstrates control over profit and loss.

- Hiring and Firing: A worker who hires, trains, and supervises his or her own staff is likely an independent contractor.

- Risk and Reward: True independent contractors may see their income go up or down based on their choices—such as how much to invest in marketing (think placing an ad on LinkedIn), whether to purchase more advanced equipment, or whether to outsource portions of a project. If a web developer invests in tools or platforms to improve efficiency, and those decisions impact his bottom line, that risk and reward relationship suggests independent contractor status.

- Contrast with Employees: On the flip side, if an individual simply receives assignments, follows instructions, and is paid an hourly or fixed wage with no say in business–level decisions, his chance for profit or loss is limited. For instance, if a delivery driver for a local restaurant works only the shifts assigned and earns based on hours worked rather than managing routes, pricing, or hiring, the driver is much more likely to be classified as an employee.

- Examples in Context: First we have an independent house painter who advertises services, bids for jobs, buys supplies, and sometimes hires assistants. This person directly manages her opportunity for profit or loss. Contrast that to a painter who shows up to a jobsite, uses company supplies, and is paid at an hourly rate according to company policy—the latter is acting as an employee.

Ultimately, the more control the worker has over the key financial components of the work, the greater is the likelihood that the worker is an independent contractor. If those financial decisions are largely out of the worker's hands, classification as an employee is likely.

D. Independence as a Business

An important way to show that the independent contractor's business is distinct from the company is for there to actually be a separate business entity. If the independent contractor has a registered LLC and other signs of a legitimate corporate structure, its true independence is easier to prove. If, in addition, it also carries relevant forms of insurance and provides benefits to its own employees, this truly helps to solidify the analysis.

Especially when the evaluation is a close one, it's wise to only contract with other entities as independent contractors, not with individuals.

VIII. Advisory Opinions in Colorado

Another option available to employers in Colorado seeking guidance on whether an individual is an employee or independent contractor is an Advisory Opinion from the Colorado Unemployment Insurance Employer Services, Audits. You will be required to submit a form with information, along with $100 and the Division will provide you with guidance on how to classify a worker. This can be helpful to put any close questions to rest. The link to the form is available here.

Other states may provide advisory opinions as well.

IX. What if We Get it Wrong?

Potential penalties for misclassifying an employee as an independent contractor can be steep. While it may be tempting to label a worker as an independent contractor to avoid the expenses associated with having an employee, misclassification can lead to serious consequences and cost in the long run.

If you haven't paid workers compensation premiums, unemployment premiums, other insurance premiums (like Colorado FAMLI Act), or federal employee withholding taxes, the fines and penalties could be extensive. The IRS may come after you. A state or federal audit may occur, which is both stressful and disruptive to the business. The state may charge you penalties for not paying unemployment compensation insurance premiums for the employees. You may need to get legal counsel to challenge state or federal findings, and the administrative review process has multiple levels.

If you think you have done it wrong in the past, reach out to legal counsel to start the process of untangling the situation and getting squared away with the government. If you are analyzing a work situation, pay careful attention to the federal and state factors that apply.

Featured Image by Rebecca Sidebotham.

Because of the generality of the information on this site, it may not apply to a given place, time, or set of facts. It is not intended to be legal advice, and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations