Who, What, and When: Recent Rulings Clarify and Expand the Ministerial Exception

2022 has been a big year for the so-called “ministerial exception,” a First Amendment doctrine that protects churches and religious ministries from government interference into their employment relationships with ministers. Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision earlier this year to deny review in a major ministerial exception case, federal appellate courts have recently issued rulings that clarify the scope and application of this important constitutional doctrine that affects religious employers.

This article discusses what these decisions mean for religious employers.

Understanding the Ministerial Exception . . . in 3D

The ministerial exception is a rule that stems from the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The rule is simple. The government must not interfere with the employment relationship between religious organizations and their ministers. But this simple rule can get complicated when trying to understand its limits.

The ministerial exception has only been formally recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court since 2012 and has had actual application in only two Supreme Court decisions, neither of which has defined the precise scope of the exception or addressed vexing questions about how broadly it applies. One can conceive of these uncertainties in three dimensions: Who, What, and When.

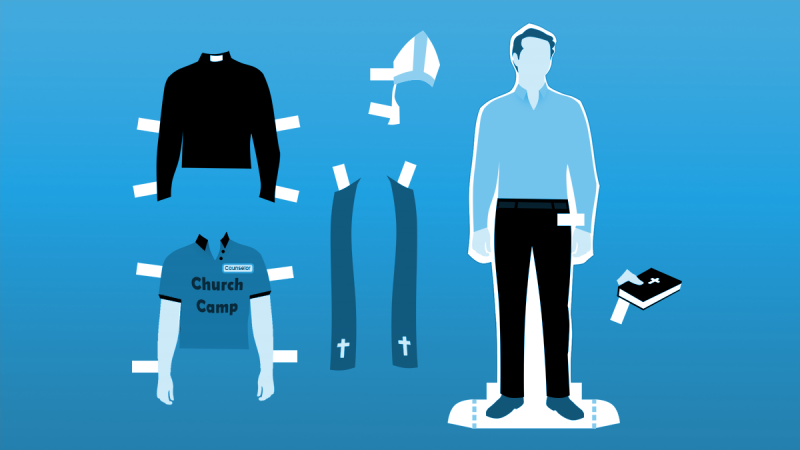

The WHO question asks which kinds of employees count as “ministers” for purposes of the exception. Everyone agrees that clergy like the parish priest and the congregational rabbi are safely within the scope of “ministerial” employment. We know that the term “minister” is broader than “clergy.” But just how much broader is it? In 2020, the Supreme Court provided some clarity to this issue by articulating a fairly simple test for ministerial employment: A minister is an employee who performs “important religious functions.” This definition still did not fully clarify the scope of the WHO issue. Are nurses at religious hospitals covered by the exception? What about camp counselors, sports coaches, and many other employees of religious institutions? How far does the exception extend in the WHO dimension? The courts are still figuring this out.

The WHAT question asks which kinds of legal claims or liabilities are barred by the exception. It’s certain that the exception immunizes churches and ministries from liability for statutory claims based on theories of discriminatory hiring and firing. But courts have split on whether the exception exempts religious employers from other liabilities such as wage-and-hour violations, workers’ compensation requirements, contractual breaches, and workplace torts. This dimension of the exception is also unclear and disputed.

The WHEN question asks at what stage in legal proceedings the exemption applies to exculpate a religious employer. Is the ministerial exception a complete jurisdictional bar to claims against religious employers, allowing them to dismiss lawsuits without needing to litigate them? Or is it rather an affirmative defense that an employer must plead and prove at trial only after incurring the trouble and expense of litigating the case through discovery? Courts have also split on this issue.

The WHO, WHAT, and WHEN questions of the ministerial exception are still being fleshed out in the federal courts. Two recent federal appellate decisions address these questions and provide some meaningful clarity.

Diminishing the Domain of Defense: Tucker v. Faith Bible Chapel International

The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals recently clarified the WHEN issue with its decision in Tucker v. Faith Bible Chapel International. The facts of the Tucker case are simple: In 2017, a long-time science teacher and chaplain at a Christian school in Colorado was fired after parents objected to a chapel presentation he gave on the topic of race. The teacher sued the school, alleging that it had violated federal anti-discrimination law by retaliating against him for opposing a racially hostile environment. The school immediately moved to dismiss the teacher’s lawsuit on grounds that the court lacked jurisdiction because the teacher was a minister, and his claims were barred by the ministerial exception. The district court denied the school’s motion.

To appreciate the significance of this ruling, it is important to understand the difference between a jurisdictional defense and an affirmative defense. A jurisdictional defense is one that can result in a legal claim being dismissed at the outset of litigation without addressing a claim’s factual merit. Federal courts have limited jurisdiction and if a plaintiff asserts a claim that is outside the jurisdiction of the court, then the defendant can get the claims dismissed without needing to litigate at length.

An affirmative defense is different: a defendant must assert it in its answer and has the burden of proving it through the evidence. If a defendant meets its burden of proving an affirmative defense to a claim, then it can move to have the claim dismissed on summary judgment (which is typically much later in litigation), and if that fails, it can try to prove its affirmative defense to the jury.

A jurisdictional defense presents a question of law that a court can rule on at the outset, and an affirmative defense presents a question of fact that must be determined by a jury or finder of fact. This results in an important practical difference with respect to when each defense can be successfully asserted. A defendant can assert a jurisdictional defense as soon as the lawsuit is filed and can quickly move to have the action dismissed. But successfully asserting an affirmative defense requires the defendant to gather evidence to meet its factual burden of proof to support the affirmative defense it is claiming. Therefore, an affirmative defense might still require a defendant to litigate the claims through the discovery phase and sometimes even through trial. From a defendant’s standpoint, a jurisdictional defense is preferable to an affirmative defense because it means that the claim is dismissed much earlier without having to litigate the lawsuit, which is extremely expensive.

In the Tucker case, the defendant school asserted the ministerial exception as a jurisdictional defense in an attempt to get the lawsuit dismissed quickly. But the trial court ruled that the ministerial exception was an affirmative defense, and the school had the burden of proving that the plaintiff teacher was a minister.

The school appealed to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, which affirmed the district court’s ruling. Citing to language from the U.S. Supreme Court’s two ministerial exception cases, the appellate court ruled that applying the exception “requires a fact-intensive inquiry into the specific circumstances of a given case.” Therefore, the Tenth Circuit held that the issue of whether the ministerial exception applied was not a question of law, but a question of fact that required the school to litigate the lawsuit until it could meet its evidentiary burden of showing that the teacher was a minister.

Augmenting the Ambit of Autonomy: Starkey v. Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Indianapolis

The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals recently addressed both the WHO and WHAT questions in its decision in Starkey v. Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Indianapolis, Inc. Like the Tucker case, the Starkey case involved a Christian school employee. In Starkey, the employee was fired when school officials discovered she was in a same-sex marriage, something that was contrary to the school’s Catholic teaching. The employee sued the school, asserting a variety of different legal claims.

The first issue, the WHO question, was whether the employee was a minister. The employee’s job description and employment contract made it clear that she was expected to be a “faithful Catholic” and that her duties included important religious functions such as “communicating the Catholic faith,” and “praying with and for students.” Nevertheless, the employee asserted that she was not a minister because, notwithstanding the religious functions in her job description and the fact that she was expected to teach the faith and pray with students, she never actually did those things in during her tenure. Therefore, the employee argued, her actual job functions were not religious, she was not a minister, and her claims were not barred by the ministerial exception.

Both the trial court and the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals rejected this argument. The appellate court’s decision responded to this argument as follows:

This argument misunderstands the ministerial exception. What an employee does involves what an employee is entrusted to do, not simply what acts an employee chooses to perform. Under Starkey’s theory, an individual placed in a ministerial role could immunize themself from the ministerial exception by failing to perform certain job duties and responsibilities. Religious institutions would then have less autonomy to remove an underperforming minister than a high-performing one. But an employee is still a minister if she fails to adequately perform the religious duties she was hired and entrusted to do.

Therefore, the court concluded that this employee was indeed a minister.

The second issue in the Starkey case, the WHAT question, was whether the ministerial exception applied as a defense to all of the claims she asserted. In addition to statutory claims for discrimination (which are clearly barred by the ministerial exception) the employee also asserted two tort claims against the school: Interference with Contractual Relationship and Interference with Employment Relationship.

Some courts have interpreted the ministerial exception narrowly, applying it only to discrimination claims that involve a church or ministry’s decision to hire and fire ministers. However, the Seventh Circuit, citing to several cases from other federal courts, took a broader reading of the WHAT scope. The Starkey court held that “the ministerial exception applies to state law claims, like those for breach of contract and tortious conduct, that implicate ecclesiastical matters.” The court further explained that “a claim implicates ecclesiastical matters” if it “relates to or involves the church as an institution.” The court found that these two tort claims “implicate ecclesiastical matters because they litigate the employment relationship between the religious organization and the employee.” Therefore, the court applied the ministerial exception to bar the plaintiff’s tort claims against the school.

There are two important takeaways to extrapolate from the Starkey case. First, it’s not simply the functions that an employee actually performs in fact that determines whether or not he or she is a minister. Rather, it’s what an employee is expected to do and the duties with which he or she is entrusted that matters. Second, the defense of ministerial exception is not limited to claims of employment discrimination. Rather, immunity extends to other kinds of claims that implicate ecclesiastical matters or that go to the employment relationship between the organization and the minister.

Why and How: Implications for Faith-Based Organizations

Given the clarified scope of the WHO, WHAT, and WHEN dimensions of the ministerial exceptions, religious employers must ask two final questions: WHY do these two decisions matter, and HOW should ministries respond to them?

As to the WHY question, churches and ministries should recognize that this particular point of constitutional law vitally affects them from the standpoint of legal liability. The application of the ministerial exception could mean the difference between effective management of legal risks on one hand and the possibility of expensive and burdensome litigation and exposure to liability on the other.

While these two cases are technically only binding in their own circuits, they provide some general guidance. The Tucker case speaks to the WHEN issue. Its ruling means that employers should be prepared to prove the ministerial exception as an affirmative defense through clear evidence that an employee is indeed a minister. Religious employers need to be able to meet this evidentiary burden so that claims can get dismissed on summary judgment and need not be litigated through trial.

The Starkey case clarifies the WHO issue and instructs upon the importance of job descriptions, formal written policies, and other documentation to prove an employee’s ministerial status. It also provides a broad reading of the ministerial exception’s WHAT dimension and permits religious employers to invoke that defense against a variety of legal claims.

HOW can faith-based organizations take steps to ensure the greatest possible protection and immunity under the ministerial exception? First, ministries should determine which employees they regard as being “ministers,” (i.e., those who are expected to perform religious functions). Second, for those employees who are regarded as ministers, employers should implement detailed job descriptions and written acknowledgements that provide clear evidence of ministerial status. Finally, religious employers should seek counsel from an attorney who is knowledgeable on these issues to advise on how best to assert these defenses and prevent legal liability.

_________________________________________

Featured Image by Rebecca Sidebotham

Because of the generality of the information on this site, it may not apply to a given place, time, or set of facts. It is not intended to be legal advice, and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations